As the United States government began engaging in processes of mass governmental and military expansion after World War II, the interrelationship between the military and the police dilated (Kraska, 1996; Lanham, 2021). Widely studied through technological transfers and their effects (Adachi, 2016; Delehanty et al., 2017; Katzenstein, 2020; Lawson, 2018), this phenomenon is broadly considered to lie in the economic sphere. However, police militarisation is as cultural as it is economical (Kraska, 1996), and narrative shifts surrounding crisis have often transpired into processes of mass governmental expansion—including militarisation processes (Hall and Coyne, 2013). Therefore, this dissertation will pivotally ask the question: How have government narratives surrounding war and crisis created the circumstances for continual police militarisation in the United States? Moreover, as there is an emergent sub-section of literature regarding the relationship between police militarisation and racial subjugation (Belew, 2018; Gamal, 2016; Hinton, 2021; Marquez, 2021; Murch, 2015), it is essential to understand this interrelation. Throughout this study, racial subjugation in the U.S. is analysed not only as an effect of police militarisation, but as a narrative tool used to continuously militarise police forces. Thus, a sub-question is investigated: How have racialised logics aided in creating and exacerbating militarisation narratives in the United States?

By grounding this phenomenon in the historical context, this study will focus on two key moments of narrative crisis formation—the 1960s’ anti-Communism and the ‘War on Terror’—that facilitated a mass expansion of the U.S. security state, including the militarisation of the police. Throughout the analysis, I will argue that the salient formations of crises have transformed the militarised structures of policing as elite figures; and counterinsurgency narratives have rhetorically domesticated the notion of war to shift, and critically intersect, the ontological understandings of policing and warfare. As rhetorical wars are transported into the field of domestic policymaking to protect a population from a narrated crisis, government powers proliferate, including in the expansive relationship between the military and the police.

Although this study is framed through historical analysis, it is important to acknowledge that this is not only a historical issue. The militarisation of the police, as justified by narrative frames, is ever-evolving in the modern context as it is fundamentally, wholly, and systemically a product of the American society. A cultural story is embedded in U.S. society that has transported warfare from the sphere of the foreign to the sphere of the domestic, a perpetual transcendence of borders villainising the most marginalised in our societies. The narratives studied have shaped the currents of crisis formation to justify an unending war that continues to take place on the streets of U.S. cities under the guise of the protective force of policing. Thus, this dissertation will argue that this phenomenon is ongoing, as the cultural and policy-centred shifts in the understanding of war and police are consistently shaped and reshaped by narrative crises.

Militarisation and Militarism in U.S. Police Forces

The militarisation of the police as a process that occurs through technological transfers from the military unit to the police body is widely cited (Adachi, 2016; Delehanty et al., 2017; Jaccard, 2014; Jones, 1978; Kishi and Jones, 2020; Steidley and Ramey, 2019). However, Kraska explores police militarisation as a process of cultural transfers (Kraska, 1996; 1997; 2007). In his 1996 reflexive, ethnographic study, Kraska analyses the culture of militarisation, arguing that it exists in both “macropolitical” and “micropersonal” forms (1996:423). For the latter he coins a “habitus of militarism” (1996:423), as small personal changes, such as in uniforms, occur alongside technological transfers. In a later study, he explores this notion further theorising that a “paramilitary subculture” exists in police paramilitary units by using data derived from police agency surveys at the national level (Kraska, 2007:512). What is pivotal here is Kraska develops an understanding of police militarisation that is not confined to technological transfers but also exists as a cultural facet. However, these studies predominantly focus on the militarisation of the police as a micro-reality, looking at the macropolitical effects within police units without critically examining the socio-cultural transformations that have facilitated them. Looking at narrative structures during periods of crisis can expand on notions of technological and cultural militarisation, providing the argument that these processes are shaped, warped, and restructured by social reality.

Anti-Communism and Police Militarisation in the 1960s

The intense fearmongering and mass hysteria that took place during the second ‘Red Scare’ is widely studied as an anti-Communist narrative force that dictated American social reality throughout the twentieth century (Carleton, 1987; Foster, 2000; Schreker, 2004; Selverstone, 2010). Although the literature is not as vast, a sub-section explores this narrative force as a tool used to subjugate Black communities in the 1960s through the villainization of sectors of the civil rights movement (Berg, 2007; Horne, 1986; McDuffie, 2011). Building on this, other literature shows an interconnection between Black subjugation, anti-Communism, and police militarisation in the U.S. during the 1960s (Belew, 2018; Gamal, 2016, Hinton, 2021; Lanham, 2021). Gamal uses Critical Race Theory to conduct a historical analysis of the militarised response to 1960s “racial uprisings” (Gamal, 2016:982). Focusing on J. Edgar Hoover and threat construction, she states, “advancing militarisation … meant constructing an identity for the protesters that placed them outside of state protection and in the realm of state threat” (Gamal, 2016:993), giving way to large-scale militarisation processes. Elizabeth Hinton also explores this relationship through historical analysis, particularly focusing on the uprisings in Black communities in the 1960s that met a militarised response under Johnson’s ‘War on Crime’ (2021). She found police forces were shown anti-Communist propaganda, claiming that uprisings in U.S. cities were not due to economic or social inequality but are part of the “aims of international Communism” (Hinton, 2016; The National Education Program, 1968), a view also championed by Hoover (O’Reilly, 1988). These studies pivotally reveal the interrelationship between police militarisation, anti-Communism, and racial subjugation in the U.S. domestically. However, an exploration of the interconnectedness of U.S. foreign and domestic policy that shaped the militarised structures of U.S. domestic policing will aid in developing a deeper understanding of this phenomenon.

Considerably, scholars have noted that during Johnson’s ‘War on Crime’, a shift to a law-and-order mindset facilitated a mass expansion in police powers through militarisation processes (Adachi, 2016; Gamal, 2021). However, Schrader’s historical analysis explores the importance of the Office for Public Safety’s (OPS) overseas police assistance efforts in Vietnam, which reimported counterinsurgency tactics through domestic police training programmes and arguably facilitated the shift towards this mindset (Schrader, 2019). Lanham attempts to build on Schrader’s study, linking his findings to more recent history, arguing that “racist foreign and domestic policy are two sides of the same coin” (Lanham, 2021:1414) as exposed through the ‘War on Terror’ and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests. However, Schrader’s study does not provide the empirical research that is needed to transport this argument into one that transcends a singular historical timeframe. Therefore, this study attempts to link Schrader’s research to more modern history, arguing that the processes he exposed are ever-evolving and dictated by narrative structures.

The ‘War on Terror’ and Police Militarisation in the 2000s

The notion that the ‘War on Terror’ was a product of political “myth” making is cited in the scholarship (Esch, 2010). Here, Bush heavily relied on the Manichean rhetoric of American Exceptionalism—the idea that America or American values are exemplary to other nations—to state that it was America’s “calling” or “mission” to fight in the battle of good against evil (Esch, 2010:366). Moreover, Ackerman theorises the use of “intellectual borders” in the expansion of the U.S. security state that segregated “those who were authentically American from those who were not” (Ackerman, 2021:37), exploring the creation of the ‘War on Terror’ in public consciousness as a racialised phenomenon. Military strategists and scholars alike have also discussed the use of counterinsurgency (COIN) tactics in the COIN 2006 programme as an identity-focused, population-centric form of warfare that evolved from counterinsurgency strategies used in the Vietnam War (Darda, 2020; McAlexander, 2007; Owens, 2015; Sitaraman, 2009). However, as Singh theorises, the racialised logics of counterinsurgency were not confined to aspects of foreign policy; the ‘War on Terror’ is a product of American imperialism that penetrated both the international and domestic spheres (2017).

Additionally, there is an existent section of legal scholarship that explores the introduction of the PATRIOT Act during the Bush administration, noting that a broadening of the scope of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act gave law enforcement agencies increasing access to national security intelligence (Miller, 2020). Some scholars argued that this negatively affected minority populations as it drastically increased search and seizure powers (Siegler, 2006), surveillance technology transfers, and racial profiling, particularly among Muslim men (Pitt, 2011). However, these scholars focus heavily on the PATRIOT Act as a purely legal, bureaucratic phenomenon that existed within U.S. domestic policy. Building on Singh and Schrader, this study will argue that the Act can be considered part of a larger rhetorical domestication of warfare, and its transferal into expanding policing powers was inherently racialised in its narrative formation as much as in its effect.

Theoretical Framework

This research will expand upon the theoretical framework of the political economy of crises, which infers the argument that during times of real or perceived crisis, a government increases in size, scope, and force (Hall and Coyne, 2013). Hall and Coyne’s study builds on the framework of Higgs (1987; 2004; 2006; 2007; 2012), recounting the ‘War on Drugs’ and the ‘War on Terror’ as times of perceived crisis that facilitated mass governmental expansion (2013). As Higgs states, the government maintains its power by exuding an ideology—based on specific principles, ideals, or values that are legitimated by fear (2005:448)—dictating structures of social reality to monopolise power. Moreover, during times of war or crisis, a government can increase this power in the form of “sudden bureaucratic dilation” as “the public relaxes its usual resistance to the government’s exactions” (2005:461). Due to the “paradox of government”, during a time of crisis, as a form of “protection” the government gains a monopoly on the means of force and the means of violence (Hall and Coyne, 2013:485-486). As Hall and Coyne argue, this facilitates the mutually reinforcing bureaucratic and economic interrelationship between the military and the police in the U.S. seen through budget, personnel, and technological transfers (Hall and Coyne, 2013:488).

However, the economic relationship between the military and the police is well-founded. Thus, this study attempts to provide an alternative account of this phenomenon, focusing on the narrative formation of crises that continually justifies the expansive bureaucratic relationship established by the theory. This will highlight the ‘storytelling’ processes of crises, relying on the assumption brought by Higgs (2006) and Krebs (2015) that the government provides a sense of freedom from fear (Higgs, 2006:449), or ontological security, to the civil population, which itself relies on a set and structured narrative order (Krebs, 2015:39). In times of crisis, whether real or perceived, storytelling is further exacerbated, as traditional or “underlying narratives no longer seem like common sense” (Krebs, 2015:39). This leaves space for shifts in the prevailing narrative which can, relying on traditional values or identities, impart a sense of stability and order. Shifts in narrative can then justify policy decisions that may be deemed controversial or illegitimate outside of the new narrative structure as governmental expansion is justified by the idea of civilian protection in the face of crisis (Krebs, 2015:62). As Hall and Coyne argue, this expansion exists in the facilitation of state power in general but, due to the agenda to maintain a monopoly of military force, is only exacerbated by the transferral of military powers into policing (2013). Moreover, as Butler states, “a similar ‘frame’ grounds our orientation in both (domestic and foreign) domains” (Butler, 2009:27). Here, the narratives of crises are framed as both domestic and international under the process of “effective framing” (Krebs, 2015:38), which can allow governments to fit preferred policy-incentives into the prevailing narrative structure. Thus, the real or perceived crisis is created or exacerbated by a narrative that, when framed as an ongoing war, facilitates the expansion of the security state, including in the continual militarisation of police forces.

Furthermore, as Hall and Coyne have explored, when crises are framed to both exist domestically and internationally and to have no clear end, police militarisation can continue indefinitely due to a “ratcheting up” of government spending (Hall and Coyne, 2013:490). Applying this to the narrative formation of crises, as war is ontologically structured as temporary this can provide “an argument for exceptional policies” (McIntosh, 2022:572), due to the government agenda to monopolise power in a time of crisis. However, if a war is framed temporally against a crisis that has no clear end, it is considered indefinite (McIntosh, 2022:573), allowing increasing facilitation of these “exceptional policies”. Therefore, a “perpetual crisis” (Hall and Coyne, 2013:500) means the U.S. government can create a perpetual war, increasing the expansion of police militarisation in the process. Applying this to the work of scholars such as Singh (2017) and Darda (2020) who pivotally recentre this argument to imply that the facilitation of a “permanent war story” (Darda, 2020:35) or “long war” (Singh, 2017:159) can create an increasing legitimation of wars fought “along the color line” (Darda, 2020:32). Essentially, the reframing of war as perpetual can allow a continuous criminalisation of black and brown communities and societies, as the governmental narrative equates notions of criminality and insurgency with certain racial identities to legitimise the crisis. Therefore, narratives are quintessential in understanding how the militarisation of the police can continue indefinitely; however, a body of literature focusing on the economic effects of crises has yet to uncover how these processes rely on rhetorical transferrals of power through narrative shifts.

Justification of Methodological Decisions

To effectively analyse how narratives have continually facilitated the expansion of police militarisation in the U.S., this study will employ a close reading of key documents and discourses in developing a historical account of this phenomenon. This study will journey through American political history, focusing on the time periods of 1960s anti-Communism and the ‘War on Terror’ in the early 2000s, using two key periods of crisis formation to evaluate the evolution of police militarisation and the perpetuality of the issue. As both periods were perceived as a crisis by the public and were salient in consciousness (Howie and Campbell, 2017; Schreker, 2004), existing in both the domestic and international spheres, they provide many avenues for comparison. Thus, this study contributes to the literature by providing a pivotal framework for re-interpreting historical understandings of police militarisation.

Structurally, the study is divided into two sections, firstly focusing on rhetorical narrative structure by analysing elite discourse, and secondly focusing on narrative creation through counterinsurgency processes and the rhetorical and policy-centred domestication of such processes. The analysis will initially focus on two figures, George W. Bush and J. Edgar Hoover who are appropriately labelled “narrator-in-chief” (Krebs, 2015:49) for each respective period. Bush is regarded as the founder of the prevailing ‘War on Terror’ narrative (Hetherington and Nelson, 2003; Esch, 2010), and thus evaluation of his rhetorical formulations is essential in understanding the narrative concept. Although, as Krebs states, the assumption is in the “American symbolic universe” the “narrator-in-chief” is the President (Krebs, 2015:49)—former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover is studied as arguably the most ardent anti-Communist during the 1960s (Schreker, 2004:1043)—as seen through his campaigning in transforming law enforcement (O’Reilly, 1988), alongside his public persona as exemplified by his best-selling anti-Communist manifesto (Gotham, 1992:58) Masters of Deceit (1958).

The documents COINTELPRO-Black Extremist and COIN 2006 are analysed as two initiatives that arguably transformed the narrative structure of warfare and policing in the U.S. COINTELPRO-Black Extremist consists of a compilation of memos from the FBI Director to local offices and between the upper echelons of the Bureau, discussing acquired information and counterintelligence initiatives regarding civil rights movements. Although a compilation of domestic counterintelligence documents, they are used here to examine a shift in the processes of domestic policing in the 1960s alongside a reimportation of counterinsurgency initiatives (Schrader, 2019). Comparably, the COIN 2006 document is a counterinsurgency field manual and is studied to show the transformation in the narrative structure of global policing and warfighting that obscured the roles of each. To build on the idea of reimportation and critically examine the rhetorical and policy-centred shifts in domestic policing, the PATRIOT Act is analysed alongside the manual, focusing on the increasing interconnection between the security state and law enforcement agencies.

Consideration of Positionality

Due to the subjective, post-positivist nature of this study, the author’s position in social reality is critically accounted for due to the likelihood of possessing predispositions or biases that may have impacted their analytical choices, including the lenses examined. As someone who is from the UK, the author has an outside perspective on U.S. culture. Moreover, as racial identity is consistently discussed throughout the study, it ought to be considered that the author is mixed-race; however, not Black nor Muslim—the identities most salient in this dissertation. Due to the embedded power structures that exist within racial dimensions that continually penetrate the academic discipline (Louis et al., 2016), particularly in an elitist Eurocentric institution, it is important to acknowledge this as a constituent part of social reality that may have infringed upon the subjective research.

PART ONE: ELITE RHETORIC AND THE CREATION OF ‘PERPETUAL WAR’

How Hoover Transformed the Communist Threat: A Study in the Rhetorical Domestication of Communism

Building on the theoretical framework, the rhetoric of Hoover is analysed through the lens of the creation of a ‘perpetual war’ against Communism, utilised to increase the power and influence of the FBI. As scholars explore, the U.S. government has at times created a narrative around a perceived crisis or government-termed war that has no clear end, timeline, or enemy (Darda, 2020; Kraska, 1996; Hall and Coyne, 2013) allowing militarisation to continue limitlessly. In 1956, J. Edgar Hoover stated that American Communists were “making war on a new plane” (1956:4). Throughout the 1960s, he would create this war through his rhetorical domestication and formation of a perpetual Communist menace.

Hoover had multiple linguistic techniques he gravitated towards to exacerbate the threat of Communism as perpetual, invasive and existential. By using metaphors relating to contagion, such as referring to Communism as a “virus” that had spread in “epidemic proportions” (Hoover, 1962a), Hoover reframed Communism as a disease, implying that the crisis existed as an invasive ideology that infiltrated the minds of Americans. By framing Communism in this way, Hoover created an invisible enemy that transcended geographical borders. Herewith, he established the most fear-inducing element of Communism that, like a disease, it had the power to ‘infect’ vast amounts of the U.S. public through a psychological invasion. Reducing the enemy to an intangible threat removed the limitations of the Communist enemy in its scope, size, power, or time range (Hall & Coyne, 2013), creating a socially imagined perpetual crisis fought with limitless means.

As Gotham notes, Hoover often attacked Communism, not based on any empirical measurement but based on constructed evils and threats to traditional American values or morals (Gotham, 1992). In a 1962 speech, Hoover stated, “The danger and wiles of Communism cannot be measured solely by shrunken rolls of actual party membership in this country” (1962a). In this speech, as in his other anti-Communist tirades (Hoover, 1958), Hoover did not provide empirical evidence of an internal Communist threat in the U.S. but actively denounced some of the only existing empirical evidence that proved the Communist ideology was declining in the 1960s. Therefore, by pinning the Communist threat to no real measurement, Hoover continued to create a perpetual war. Additionally, if Communism could not be measured, neither could there be a clear defeat, meaning measures considered capable of defeating the enemy were enhanced exponentially.

In addition, by using non-descript terminology that relied on ideological values, Hoover continued to emphasise that the rhetorically created crisis was perpetual and existential. By framing Communism as an ideology implanted into “the heart and mind of Americans” (1962a) and using Manichean rhetoric surrounding the “evils” (1962b) of Communism and the “moral armour” (1962a) of American values, Hoover amplified traditional narratives regarding American Exceptionalism. Here, he conveyed the idea that the threat of Communism existed in dualistic opposition to Americanism itself—as an ideology to be countered, rather than a physical threat. Therefore, Communism was an enemy like no other as it could not be defined temporally, meaning a legitimate defeat did not exist in the boundaries of time. Thus, the government could exponentially increase spending and power under the symbolic aim of defeat (Hall and Coyne, 2013; McIntosh, 2022).

Conflating Communism and Crime

Moreover, although the perpetual war transcended borders, physicality, measurements, and time, Hoover’s rhetorical techniques also helped to conflate Communism with the “crime problem” (Powers, 1975:267). Building on Powers, Hoover created the crime problem by diverting attention from individual instances of crime creating one clear symbol of criminality (Powers, 1975). However, by conflating Communism and crime, this changed the constructed meaning of criminality, not to be an issue of disobedience or individual behaviour, but based on “social pathology, or virus” (Schrader, 2019:51).

In a 1962 speech, Hoover stated, “Crime has a partner informing the common denominator of a breakdown in moral behaviour, it is the influence of godless Communism” (Hoover, 1962b). In another speech from the same year, he also called Communism crime’s “sinister partner” (Hoover, 1962a). By referring to Communism and crime as the same in their purposeful erosion of American moral standards, Hoover not only exacerbated the perpetual war but domesticated the Communist threat. Hoover’s creation of the perpetual war brought fear of a Communist invasion and infiltration through ideology into public consciousness, but with the added component of crime, the Communist threat no longer only existed on the ideological battlefield but on the frontlines of crime control. Criminality, therefore, had a new facet of meaning. Throughout the McCarthy era individual ideology could be a means for prosecution, whether believed or not (Schrecker, 2004); however, through Hoover’s rhetorical domestication, the peril of the Communist threat permeated the most prominent symbolic criminals of the time, including the juvenile delinquent, the drug trafficker, and the Black rebel.

“Racial Discord”

Arguably, the U.S. government had been criminalising identity long before the second ‘Red Scare’ (Darda 2020; Provine 2007; Singh 2017). As Singh observed, immigration to the U.S. historically was viewed as “tantamount to foreign aggression” (2017:52). Similarly, as the scholarship states, Black Americans are consistently criminalised based on government agendas to wipe out a certain ‘enemy’ population, including Communists, drug users, gangs, anti-war activists and rioters (Adachi 2016; Belew 2018; Darda 2020; Gamal 2016; Hinton 2021; Lanham 2021; McDuffie 2011; Moore 1981; Murch 2015). The ‘Communist threat’ was also racialised. Particularly in the 1960s, a view that Asian people were more susceptible to Communist ideologies was advanced by American forces in Vietnam (Melamed, 2011). Additionally, this racist dogma was applied to Black communities domestically in the U.S. (Darda, 2020).

Hoover championed this racist dogma, as he sought to associate social movements and unrest within Black communities at the time with the crime problem and the Communist threat. In a 1964 speech, he stated, “the Communists in this country had organised very intensely a drive to infiltrate into the racial discord and discontent in the country” (Hoover, 1964). There are multiple layers in the way this sentence is phrased. First, he states that “racial discord” is being “driven” by Communists—villainising civil rights movements as part of a wider agenda to overthrow the government (Gamal, 2016). Furthermore, Hoover’s use of the term “racial discord and discontent” is widely applicable and non-descript. By using this non-descript terminology, Hoover could pin Communist infiltration onto almost any Black emancipatory movement of the time as multiple waves were sweeping through the country (Hinton, 2021; Joseph, 2009; Zanden 1963). However, focusing on the context of the speech—it is reasonably assumed that this was retaliatory to the large-scale rebellions in majority Black communities in the mid-to-late 1960s (Hinton, 2021), which Hoover aimed to associate with revolutionary thought (O’Reilly, 1988). Thus, although the Marxist philosophy was harboured by some in the civil rights movement (Joseph, 2009), the characterisation of Communist insurgency bridged any reality within Marxist thought. As Hoover rhetorically transformed Communism into a perpetual crisis, he constructed the threat to be one that was vast, sweeping the U.S. population, and that could be found in every sector of the civil rights movement.

Moreover, the context of Hoover’s 1964 speech can be critically evaluated with the rhetorical aim to invoke police militarisation in majority Black communities. Focusing on the proximate context, Hoover set up a new FBI office in Jackson, Mississippi after three civil rights workers went missing—which Hoover deemed a hoax (Hoover, 1964)—to keep a closer eye on the movements in the area. Here, he actively expanded the scope of the FBI—localising the force substantially in its training mechanisms and transfers of security intelligence to police forces (Hoover, 1969). As Hoover stated in his 1969 annual report, “the riots and racial disturbances which have plagued the nation since 1964 have materially abated” (1969:22-23). Taking this into account alongside the fact that federal allocation for local police forces increased from nothing in 1964 to $300 million by 1970, including transfers of surplus military equipment produced for the Vietnam war (Hinton, 2021:23)—the uprisings were ‘quelled’ by heavily militarised police units. The localisation of the federal government during the 1960s, highlighted through Hoover’s initiatives, reflected a larger trend in the increasing access of law enforcement agencies to federal funds and military-grade equipment (Adachi, 2016). By framing these riots and rebellions under the idea that the “racial discord” was fuelled by a Communist threat, Hoover rhetorically domesticated and reframed Communism as a perpetual crisis, allowing a mass expansion in government power. Implying the Communist threat had saturated the civil rights movements only exacerbated this, as he reframed one of the most enduring social issues in the U.S. as an existential security threat.

How Bush Transformed the Terrorist Threat: A Study in the Rhetorical Domestication of Terrorism

Creating the ‘Perpetual War’

Continuing to build upon the established theoretical framework, like Hoover, Bush used rhetoric to frame the ‘War on Terror’ as a perpetual crisis, creating an “unremitting war” (Hall & Coyne, 2013:500) to facilitate government expansion. To create a salient narrative in public consciousness of a vast, endless threat to the cultural formation of American ‘ideals’, Bush continuously propelled the notion that the ‘War on Terror’ did not start nor end in Afghanistan or Iraq but, as he stated in his 2001 speech announcing the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, “the battle is broader” (Bush, 2001a:76). By using a dichotomous structure, Bush attempted to rhetorically transform the terrorist threat to be one of “fear” that could only be defeated by the American Exceptionalist conceptualisation of “freedom”, using this to both justify invasion through “freedom’s advance” (Bush, 2006c:400) and “spreading the hope of freedom” (Bush, 2006c:406), so Americans domestically could live “free from fear” (Bush, 2001a:76). As Bush expanded the boundaries of enemy creation, he legitimated government expansion by relying on creating a sense of ontological security amongst the population, to be free from fear itself (Higgs, 2005). The prevailing narrative thus entrenched the idea that the terrorist threat was not physically or temporally limited.

This rhetoric surrounding a perpetual crisis is particularly prominent in Bush’s later speeches, as although stark, 9/11 was ever-growing distant in American public memory. Bush stated in a 2006 speech “We cannot let the fact that America has not been attacked since September the 11th lull us into the illusion that the terrorist threat has disappeared. We still face dangerous enemies” (Bush, 2006b). By using the term “illusion” Bush solidly grounded the idea that it was a myth to believe terrorists were not lurking within U.S. borders as terrorism still provided an endless ideological threat. Moreover, like Hoover, here Bush disregarded material reality when creating the terrorist threat and denounced the idea that terrorism was less threatening in 2006 than it was in 2001. By using non-descript terminology when describing terrorists as “dangerous enemies” Bush propagated the narrative that terrorism, or the terrorist, could not be defined by a certain state or group but it was the ideology that the terrorists harboured that provided the greatest threat to the U.S. He directly reinstated this notion by proclaiming that the American strategy included “defeating [terrorists’] hateful ideology in the battle of ideas” (Bush, 2006c:395) describing the ‘War on Terror’ as “the great ideological struggle of the 21st century” (Bush, 2006c:408). By pinning the terrorist threat to a matter of defeating an ideology, Bush legitimised the perpetual war, creating a crisis with “no clear enemy and no clear end” (Hall & Coyne, 2013:500), allowing the endless pumping of resources and spending into defeating an enemy that had no real means of defeat.

Breaking down the “Wall”

As Bush created a perpetual, faceless enemy, he also rhetorically domesticated the threat, actively promoting a breakdown between U.S. law enforcement and security intelligence. Particularly through the introduction of the PATRIOT Act, Bush could create a narrative of a fundamental flaw in the U.S. security system that allowed terrorists to exploit the “gaps” between law enforcement and intelligence (Bush, 2006b), due to the metaphorical “wall” that separated criminal investigators from intelligence officers (Bush, 2006b). Thus, the narrative coincided that the 2001 PATRIOT Act “tore down the wall” (Bush, 2006b), facilitating intelligence and technological transfers from the Intelligence Community (IC) to law enforcement agencies, drastically increasing the powers of police units (Brooks, 2014). To legitimise this action, Bush rhetorically blurred the boundaries between policing and warfighting.

Indeed, just as Bush created the ‘War on Terror’ by taking a terrorist attack and transforming it into a direct attack on America and Americanism, Bush also expanded the scope of the war by placing more issues of domestic policy into the “war category” (Brooks, 2014:586). By stating that the ‘War on Terror’ was a “two-front war” (Bush, 2001b), one operating both domestically and internationally, he recentred law enforcement as a leading faction in said war. He then consistently sought to expand warfighting as a power in domestic criminal investigation bodies through an active attempt to change “the culture of our various agencies that fight terrorism” (Bush, 2001b). By “changing the culture” of bodies of criminal investigation to merge with bodies of warfighting, here he aligned the interests of military action and policing, to further embed a militarised culture in units that traditionally concerned domestic criminal investigation.

Moreover, through the PATRIOT Act and Bush’s rhetoric surrounding it, he also amended the notion of criminality in line with the terrorist threat. In his 2006 speech extending the PATRIOT Act, he stated that “the bill gives law enforcement new tools to combat threats to our citizens from international terrorists to local drug dealers” (Bush, 2006b). By emphasising that the PATRIOT Act, not only aimed to thwart domestic terrorist threats but expanded the powers of policing in the scope of local criminality, he changed the notion of criminality to concern the same security intelligence as international warfare. Moreover, by using the terms “combat” and “threats”, this only served to re-emphasise this point. Here, he took a matter of criminal activity and rhetorically transformed it to exist on the same plain as an insurgent threat to the U.S., only expanding the scope of police powers to defeat the rhetorically created enemy.

As Bush created a direct dichotomy between American values and ‘Islamist terrorism’ he created a narrative that promoted the subjugation of Muslims and Arabs. By neglecting to differentiate types of Islamic extremism in the Middle East, he instead clumped ‘terrorists’ into a “monolithic category” (Esch, 2010:376). As he consistently emphasised that radical Islam and terrorism were a threat to “America and other civilized nations” (Bush, 2006a:424), he played on the constructed dichotomy of “civilization vs. barbarism” (Esch, 2010:370). As Esch argues drawing on Edward Said (1978), Bush subversively implied the Muslim and Arab world was one of violent extremism that could only be cured through America’s neo-imperialist intervention (2010). Just as similar rhetorical assertions were used to create an American Exceptionalist dichotomy during the Cold War, Bush relied on notions that extremist ideologies were embedded in Islamic societies, stating that Middle Eastern countries “allied themselves with the Soviet Bloc and with international terrorism” (Bush, 2003:182). As he subversively regurgitated an already existent racist dogma—the notion that people of colour were more susceptible to Communist ideologies (Darda 2020; Melamed, 2011)—he also expanded this framework to encompass all ‘extremist’ ideologies. By making swathing accusations regarding the harmful impact of ‘radical Islam’, using dualistic assertations to claim that it represented fear, evil and barbarity, Bush created a narrative depiction of ‘the enemy’ in American public thought as purely a product of the Arab-Islamic world that existed in opposition to American values.

However, this demonisation of identity was not confined to the Middle East, as Bush consistently criminalised the Muslim-Arab identity through rhetoric surrounding the PATRIOT Act. As scholars have emphasised, the PATRIOT Act threatened the civil liberties of the U.S. public by extending the powers of law enforcement to conduct search and seizure operations without a warrant (Ackerman, 2021; Pitt, 2011; Siegler, 2006). Adding to this, not only did this threaten the general civil liberties of the U.S. public through concerns surrounding Fourth Amendment rights (Ackerman, 2021), but Muslim and Arab communities were primarily targeted by this legislation due to an increase in racial profiling in conducting unwarranted searches (Pitt, 2011). The racialised logics that were already existent in search and seizure policing (Murch, 2015) were then exacerbated by Bush’s narrative formation. As Bush stated in a 2001 speech, the PATRIOT Act aimed to “identify, to dismantle, to disrupt, and to punish terrorists before they strike” (Bush, 2001b). By propagating this narrative that the terrorist threat walked amongst the U.S. population and must be found out and punished “before they strike” it delved into some of the fundamental processes of stereotyping that surrounded search and seizure policing in the U.S. Just as certain modes of dress became associated with gang and drug crime in Black communities in the 1980s leading to unreasonable searches (Murch, 2015:166), stereotypes surrounding ‘terrorism’ alongside the expansion of search and seizure laws gave way to further discrimination towards American Arabs and Muslims (Pitt, 2011:56). Thus, as American Arabs and Muslims were marked with the narrated dichotomy Bush had created during the ‘War on Terror’, an increasingly militarised police force was allowed to launch a war on these communities as these racialised logics, formed by crisis, aided in the perpetual expansion of government powers.

PART TWO: THE TRANSFORMATION OF WARFIGHTING AND POLICING THROUGH THE COUNTERINSURGENCY PROCESS

How Counterinsurgency in Vietnam Reshaped U.S. Policing—An Analysis of the COINTELPRO Documents

Creating the Counternarrative

In the 1960s, as the U.S. engaged in anti-Communist warfare in Vietnam, the military also attempted to argue for an “alternative vision” (Gurman, 2013:73) that would dissuade Vietnamese people from supporting Communism. Thus, the U.S. military launched a counternarrative to introduce a law-and-order centred society in Vietnam, relying on psychological operations (PSYOPs)—considered a “sideshow” to the Vietnam war (Kodosky, 2015:173)—as part of a militant counterinsurgency campaign. By creating a second war to win the “hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people” (Dillard, 2012:60), the U.S. army engaged in new territory by combining warfighting, sociocultural intelligence gathering (Dillard, 2012) and ultimately, global policing (Schrader, 2019). The military attempted to spread the American ideals of law-and-order and liberalism throughout the Vietnamese population. By attempting to discredit the Viet Cong, and consistently advance their formulated counternarrative, they continued to attach the labels of “Communist” and “subversive” to those who portrayed resistance to these ideals (Schrader, 2019:271). By relying on infiltrating the identities and ideologies of the Vietnamese people, they attempted to build a state around the law-and-order narrative.

However, as Schrader recounts– counterinsurgency was reimported. As the Office of Public Safety (OPS) engaged in global police assistance efforts, they also allowed mass technological transfers and police training during Johnson’s ‘War on Crime’ (Schrader, 2019). As crime prevention and law-and-order became the “first line of defense” in Vietnam, this transformed counterinsurgency into policing (Schrader, 2019:80). Through reimportation, domestic policing was then transformed into counterinsurgency, as the “first line of defense” against domestic insurgency was the police (Schrader, 2019:81). Hoover championed this structural transformation in policing (Schrader, 2019:268), which will be discussed through the analysis of the COINTELPRO documents, a “domestic war program” (Moore, 1981:11) that targeted “revolutionaries”, “Communists” and “subversives” within U.S. borders. By using a set of psychological operations attempting to dissuade populations from supporting ‘insurgent’ groups in favour of the government-proposed counternarrative, COINTELPRO transformed the structure of U.S. policing as the FBI intertwined intelligence, security, and law enforcement into one programme to eliminate ‘insurgent’ threats.

Focusing on the ‘Black Extremist’ division of the COINTELPRO programme, the counternarrative, as in most counterinsurgency strategies, focused not only on certain individuals or groups—but on entire populations or communities (Owens, 2015; Schrader, 2019). This manifested through attempts to dissuade Black communities from supporting civil rights narratives. The FBI fashioned counternarrative surrounded the idea that Communist and revolutionary movements were threats to the communities targeted, did not represent the true interests of Black communities, and rather had infiltrated these communities through insurgent invasion. In creating the counternarrative, the FBI utilised multiple techniques to stoke fear into Black communities of a subversive threat representing a crisis to American values. By furnishing reports to TV stations (COINTELPRO, 1969b:95), newspapers (COINTELPRO, 1968c:7-8; 1969b:141) and creating fake anonymised letters and pamphlets (COINTELPRO, 1968d:35; 1969c:157), the FBI consistently regurgitated rhetoric that the civil rights movement had been co-opted by insurgents. They strived to “eliminate the façade of civil rights and show the American public the true revolutionary plans and spirit of the Black Nationalist movement” (COINTELPRO, 1968b:119), by fabricating information, and alienating those involved from their communities.

Throughout the documents, the term ‘Communism’ is used widely and leniently. A 1969 anonymous letter mailed by the FBI to estrange a Black Panther Party (BPP) member from a church stated, “some statements he has made both in church and out have led me to believe he is either a Communist himself, or so left-wing that the only thing he lacks is a card” (COINTELPRO, 1969f:42). This idea that the insurgent threat was more subversive than the ‘card-carrying Communist’ created a wider programme of countering insurgency, that did not only counter ‘insurgents’ but attempted to alienate any individual who held revolutionary, socialist, or left-wing views from their communities. Once again, this strategy, used in Vietnam as a form of pre-emptive counterinsurgency (Schrader, 2019), or ideological policing, was then only exacerbated intelligence and technological transfers to local police forces who directed militarised actions towards communities already targeted by the initiatives.

The Security State and the Police

Another form of strategy the FBI utilised throughout the COINTELPRO operations consisted of furnishing information to local police forces to facilitate raids and arrests—treating the police as a body in the counterintelligence initiative. This relationship may be more expansive than the documents entail as individual FBI offices did not need approval from the Director to furnish information to local police in many cases (COINTELPRO, 1968d:165). However, the limited documentation still exposes the expanses of this relationship. By implementing direct training programs in certain divisions focusing on Black Power movements (COINTELPRO, 1969e:117), the FBI expanded the sphere of national security, stretching the concept to incorporate anti-Communist activities in the field of law enforcement and local policing (Schreker, 2004:1046). Moreover, the Bureau directly furnished intelligence to police forces to schedule arrests to further the FBI’s agenda, through public humiliation of Black leadership (COINTELPRO, 1969a:123), or interrupting scheduled campaigns or protests (COINTELPRO, 1969e:27; 1968d:91). Much of the leaked information was then used to facilitate raids and civil forfeiture, some of which resulted in assassinations, including that of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago, 1969 (Haas, 2010). These raids, often based on minor infractions such as drug charges, only known to the police through in-depth FBI tracking, had mass repercussions on Black communities across the U.S., as individuals were forced to move from their homes (COINTELPRO, 1969b:225), arrested, brutalised, or murdered.

Looking at these documents alongside existing evidence of counterinsurgency reimportation, it is ever-more conclusive that COINTELPRO’s ‘counterintelligence’ was a form of domestic counterinsurgency strategy. In 1969 the first Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) unit was released on the Los Angeles section of the BPP as the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) began “informally consulting” with the Marines (Gamal, 2016:995) relying on OPS efforts (Schrader, 2019:23), all the while being furnished information from the FBI. This led to a long expansion of the powers of SWAT, and by 2014 the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reported that 80% of SWAT raids were conducted to serve search warrants, mostly for drug offences (Jaccard, 2014:2), adding to a long and violent history of racialised drug policing in the U.S. (Provine, 2007). Although, COINTELPRO was revealed and condemned as an illegal operation as exposed by amendments to the Freedom of Information Act (Churchill and Vander Wall, 1990), the reimportation of counterinsurgency tactics left a mark on the politics of U.S. policing. However, just as the effects of COINTELPRO exacerbated Black subjugation; the narratives that justified its formation were also inherently racialised.

“Black Extremists” and the “Riots”

As in foreign counterinsurgency operations, identity was a critical in both creating and subverting the threat of internal insurgency within the U.S. By focusing on the broad conceptualisation of ‘Black Extremism’, Hoover and the FBI used riot-control policies to criminalise movements, allowing militarised policing to spread through entire communities. Although the Kerner Commission investigating the early 1960s uprisings in majority Black communities found that the major reasons for the uprisings were “pervasive discrimination and segregation” in economic life (Kerner et al., 1967:22); using racialised logics to frame the uprisings as “riots”, Hoover aimed to transform the narrated crisis into a matter of Communist insurgency (O’Reilly, 1988). This created the framework for COINTELPRO-Black Extremist’s launch in 1968 as Hoover was committed to expanding the size and scope of the FBI in the “realm of counterintelligence” (O’Reilly, 1988:100) in response to the crisis. Therefore, the entire narrative formation that produced COINTELPRO was racialised, as it fought to treat uprisings in communities based on drastic and vast inequality under the façade of an insurgent crisis, with the aim of discrediting the civil rights movement.

Throughout the documents, this agenda is consistently mentioned, as criminalising Black communities under newly introduced riot-control laws was high priority for the FBI and local police forces alike. Throughout, it is consistently re-emphasised that FBI agents and informants were actively searching for information based on possible violations of anti-riot laws (COINTELPRO, 1969a:28, 172; 1969c:66; 1969d:33, 73, 1969e:26, 101) introduced through the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Zalman, 1975). Under the law, they facilitated the arrest of activists passing out flyers (COINTELPRO, 1968a:7) and individuals travelling to attend protests who were already under the surveillance of the FBI (COINTELPRO, 1969e:27), justified as attempting to “incite a riot” as criminalised by the Act (Zalman, 1975:897). Moreover, as in counterinsurgency in Vietnam, programmes were seen as more efficient when they were community-centred (Owens, 2015). Through COINTELPRO, police were given further access to use a “geographic application of force” (Murch, 2015:164) on already geographically segregated communities (Wilson, 2022) meaning entire communities affected by uprisings were more likely to be policed as if involved in an insurgency.

Furthermore, the police also stereotyped those associated with the civil rights movements based on their “dress and actions” (COINTELPRO, 1968e:108) as exacerbated by furnished FBI intelligence and narrative construction. As the FBI released public sketches to news media to “exemplify the type of individual usually connected with the BPP” (COINTELPRO, 1968e:165), they directly associated young Black men who dressed in a certain way with criminality and insurgency. Moreover, similar methods were used to create an insurgent caricature for the police to be “much more alert for these black militant individuals” (COINTELPRO, 1969g:14), meaning local police had the objective to increasingly exacerbate their already well-documented prejudice and brutality (Balto 2013; Taylor, 2013). Overall, the way J. Edgar Hoover relied on drug raids, anti-riot laws and blatant racial stereotyping to conduct a militant counterinsurgency operation only gave way to a transformation in the sphere of law enforcement, one that saw crime as insurgency and policed Black communities as if in a warzone.

COIN 2006, the PATRIOT Act, and How the ‘War on Terror’ Brought Back 1960’s Counterinsurgency and Policing Tactics

Creating the Counternarrative

Throughout Petraeus and Amos’s 2006 counterinsurgency manual, they examine insurgents’ use of narrative surrounding identity to mobilise parts of the population. They define narrative as “the means through which ideologies are expressed and absorbed by members of a society” (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:65), essentially a form of cultural story used to facilitate ideological shifts. Petraeus and Amos note that “Islamic extremists use perceived threats to their religion by outsiders to mobilize support for their insurgency and justify terrorist attacks” (2006:22). What is crucial in this assertion is that it is implied that insurgents had supposedly mobilized components of identity to imply that “perceived threats” required revolutionary action. Critically, the counterinsurgents transformed this narrative by relying on adjacent identities and perceived threats to create a salient counternarrative. Here, the U.S. had to “decode” narratives and create counternarratives to justify their involvement and legitimate their actions (Darda, 2020:169). By arguing that consistent engagement with cultural facets of the population could allow counterinsurgents to create a counternarrative, COIN attempted to sway the majority of the population to U.S. interests (Darda, 2020). As the manual often references T.E. Lawrence (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:15, 16, 40), it essentially asks the counterinsurgent to immerse themself into the culture of the population, acquiring a fully formed perception of the insurgent’s identity and how to co-opt that identity. As scholars have noted, using identity to create cultural counternarratives is an inherently racialised process (Darda 2020; Melamed 2011; Singh 2017). These counterinsurgency tactics relied on taking a ‘failing state’ and transforming it into a system that propagated traditional American ideals. Particularly through counterinsurgent policing, this focused on a subset of the population or insurgency as a “hazard to the modernization process” (Singh, 2017:63), using identity as a co-optable cultural narrative. However, to further legitimise the counterinsurgency process, Petraeus and Amos consistently focused on ideology as constituent of identity.

The COIN 2006 documents emphasise the importance of ideology in creating the cultural narrative and the counternarrative. Here, the U.S. military pinpointed identity as a form of cultural narrative that could mobilise vast amounts of the population. Therefore, by integrating the notion of identity as previously discussed, the counterinsurgents could further legitimise the war by basing it on a salient fear—particularly that of subversion, encroachment, and infiltration (Mulholland, 2012:225)—the rhetorical creation of the terrorist threat. As a result, the rhetorically created ideology became a crisis with revolutionary and world-altering potential. To analyse the insurgent narrative, Petraeus and Amos frequently compared the ‘War on Terror’ to the Vietnam War by accentuating the importance of both Islamic extremists and Marxists holding an “all-encompassing worldview” as well as being “ideologically rigid and uncompromising, seeking to control their members’ private thought, expression, and behaviour” (2006:27). Moreover, they even state that “ideologies based on extremist forms of religious or ethnic identities have replaced ideologies based on secular revolutionary ideals” (2006:16). This essentially implied the ideological counterinsurgency efforts used in the ‘War on Terror’ were a direct evolution of that used as an anti-Communist force during the Vietnam War. Identity was particularly prominent in this evolution. By recognising and identifying the ideologies behind insurgency, the counterinsurgent then sought to create the narrative to undermine these ideologies by exploiting alternative narratives that existed within the population (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:193) or by mobilising another salient political leader (68). By testing the waters with counternarratives surrounding rhetorical notions of national liberation or redemption, the U.S. would see what resonated within the population, winning the trust of opinion-makers in the process (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:193) and intending to gradually turn the U.S.-proposed narrative into a salient element of cultural thought. While producing an alternate ideology, counterinsurgents would enforce their created cultural story on a population through a process that consistently interchanged the roles of warfighting and policing.

Policing the World

Throughout the manual, Petraeus and Amos emphasised the interrelationship between the U.S. military and the host nation (HN) police forces, as well as the role of the U.S. military at times operating as a police force. Notably, they originally denounced the notion of the U.S. military acting on behalf of police; however, they stated that President Bush, as Commander-in-Chief, had signed a decision directive in 2004 giving the U.S. Central Command responsibility for “coordinating all U.S. Government efforts to organize, train, and equip Iraqi Security Forces, including police” (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:234-235). This meant that U.S. forces were given a directive in Iraq to actively militarise Iraqi police forces through equipment and training programs. Furthermore, counterinsurgency and global policing in Iraq and Afghanistan were advertised by Petraeus and other officers as a form of humanitarian warfare with their ideas of “population-centric counterinsurgency” (Owens, 2015:246). However, as Owens argues, populations traded off one form of violence in return for another (Owens, 2015) as counterinsurgents attained “a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence within a society” (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:47) through their crisis-centred counternarrative. Although the manual tried to imply this form of ‘humanitarian’ counterinsurgency did not force American values onto the populace and provided a legitimate alternative to the insurgent force (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:137), by institutionally restructuring the HN through American military systems they imposed a “marshal cultural narrative” (Darda, 2020:170) that would enforce U.S. norms. By consistently blurring the line between the U.S. military and the HN police force (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:154), whilst also linking the role of warfighting and policing in the HN (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:161), the U.S. took on a role that transported American ideals of law-and-order and enforced these ideals with military capacity. Although Petraeus and Amos attempted to differentiate the roles of the military and policing, as the U.S. military acted on behalf of HN police forces and counterinsurgents were able to switch between the role of police and military officer (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:162), the bodies became inextricably linked.

Moreover, as the 2006 documents blur the line between warfighting and policing, the manual also makes an active attempt to equate insurgency and criminality as a counterinsurgency strategy. As Petraeus and Amos stated that criminals may be attracted to the “romanticism” of insurgency (2006:21), and insurgent forces linked themselves within criminal networks (2006:76), they also stated that “when insurgents are seen as criminals, they lose public support” (2006:35). Therefore, the legal system “in line with local culture” (2006:35)—either created or propped up by the U.S.—was meant to focus on treating the insurgents as criminals as a form of HN government legitimacy enhancement (2006:35). Here, by blurring the line between warfighting and policing, and criminality and insurgency, Petraeus and Amos set up a state in which criminals and insurgents were interchangeable terms, and communities could either be policed or fought. Moreover, by embedding the idea of law-and-order in state-making, as police forces and internal security structures became the “first line of defence” (Schrader, 2019:79), they re-emphasised that the rule of law triumphed over all social grievances whether this showed its head through insurgency or criminality. By proclaiming the rule of law as the first major aspect of state building (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:34) they, therefore, may have addressed other forms of social and economic inequality—but grievances led by insurgents were policed, discredited or the insurgent eliminated (Petraeus and Amos, 2006:26). As Petraeus and Amos stated, the police were the frontline of the COIN force (2006:153), and by having police forces at the front of both a state-building and war-fighting operation, perhaps had repercussions on the cultural understanding of the police itself.

Reimportation: Domestic Policing during the ‘War on Terror’

As Schrader argues, counterinsurgency in Vietnam transformed domestic U.S. police forces by creating the law-and-order ideal that has shaped U.S. policing until today (Schrader, 2019). Similarly, this can be extended to the ‘War on Terror’ by analysing the law-and-order rhetoric that global policing championed under the guise of counterinsurgency and the increasing interrelationship between the security state and U.S. domestic police forces. Looking at the PATRIOT Act alongside COIN 2006, as the military consistently engaged in forms of global policing, U.S. domestic police forces were given increasing access to electronic security intelligence supposedly used to track terrorist threats, which could also be used for criminal investigations (Siegler, 2006:18). This expanded the functions of the U.S. police force as they were transformed into a body meant to fight the ‘War on Terror’ domestically alongside military forces. By expanding both the economic relationship (Hall and Coyne, 2013) and the cultural relationship of the military and the police, Bush gave access to continually interlink the existing bodies. Therefore, the war was fought on two frontlines, as criminality and insurgency became interchangeable, as did crime control and “low-intensity conflict” (Kraska, 2007:502). As cultural rhetoric, policy change, and global policing expanded the size and scope of U.S. government influence both domestically and globally, the idea of infiltration and subversion washed over the U.S. population (Ackerman, 2021). The ideological battle was so heavily intertwined with racial identity, and the PATRIOT Act consistently criminalised those from Muslim and Arab backgrounds through warrantless searches (Pitt, 2011). Thus, the breakdown in boundaries between the security state and policing can be deemed part of a larger cultural transformation in the way the national security state operated. The government-created narrative of crisis justified the fundamental breakdown of the limits of these bodies globally and domestically. A cultural shift took place—as counterinsurgents policed the Middle East, domestic police forces increasingly engaged in counterinsurgency techniques through the collection of security intelligence. The meaning of the police transformed, as it became a body upholding law-and-order through warfighting.

Summary

In summary, this study provides an in-depth historical account of the way narrative formation restructures notions of war and crisis to continually justify the militarisation of U.S. policing. Analysing the discourse of J. Edgar Hoover and George W. Bush gave focal insight into how anti-Communist rhetoric and the rhetorical formation of the ‘War on Terror’ domesticated issues of foreign policy to provide a perpetual crisis that needed a perpetual war to tackle. Moreover, through analysing the documents COINTELPRO-Black Extremist and COIN 2006, this study also provided critical insight into the narrative formation of warfare and policing in and outside of the U.S. By discussing counterinsurgency processes, this study allowed a critical examination of the way the law-and-order narrative is structured by warfare and continues to justify police militarisation in the U.S. through its rhetorical and policy-centred reimportation. Moreover, as the elite rhetorical restructuring of narrative crises and the narrative shifts through counterinsurgency formation and reimportation both heavily relied on racialised logics, this study can conclude that there is a critical interlinkage between the narrative structure of war and crisis, racial subjugation, and police militarisation. Overall, this dissertation delivers an analytical historical account of how police militarisation in the U.S. does not wholly lie in the economic sphere; on the contrary, it is exacerbated by narrative shifts surrounding crises, which have transformed the ontological structure of the police as a body, domesticating warfare in the process to continually justify the launching of technologically and culturally militarised units on minority communities.

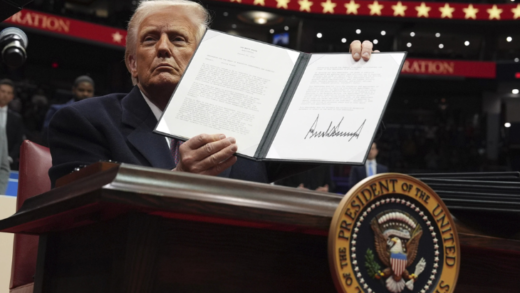

Continuing the Discussion: The Trump Administration

Although this analysis frames the use of narrative structure in police militarisation through its historical context, this phenomenon is far from purely historical. In contrast, so long as narratives continue to frame real or perceived crises as existential security threats, police militarisation will continue exponentially. A point of comparison with these historical analyses is within the Trump administration, particularly surrounding the use of narrative crises during the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in 2020.

Some see Trump as an exception in the U.S. presidency due to his reliance on populist rhetoric and disregard for democratic values (Kellner, 2018). However, as scholars such as Nikhil Pal Singh have noted, this is a fallacy—Trump is a product of American culture (2017), and his narrative creation is analogous to that of former Presidents and narrators-in-chief. Trump is, in fact, “the creature of the long war; and it now appears that he wants to bring the war home” (Singh, 2017:159). Through rhetorical transformation, Trump reignited the Communist long war, marking BLM protestors as “Marxists” (Trump, 2020a; Trump, 2020b), relying on counternarratives similar to that used in the counterinsurgency process by stating that BLM is “bad for Black people” (Trump, 2020b) and the U.S. government represents an alternate ideology acknowledging the interests of these communities. However, once again this is not limited to history. Even in Trump’s 2024 pledge in the primary elections, he stated that “terrorists are invading our Southern border” (Trump, 2024). By relying on other perceived crises in public consciousness—that of immigration and prominent rhetorical notions of the terrorist threat—he continuously attempts to reshape the identities of Mexican-Americans and immigrants aligning them with terrorism and insurgency to be both warred and policed.

Overall, the discussion is far from over; the narrative structure that shapes U.S. policing is continuously regurgitated, creating new crises and new wars to police them. As the perpetual crisis continues to loom, the expansion of the interrelationship between the military and the police will not heed. To keep understanding this phenomenon it is crucial to examine the narrative structures that are created and continuously repurposed by modern administrations.

Limitations and Recommendations

As reflected, although this study provided an in-depth historical account of the militarisation of the U.S. police, it is limited in its temporal focus. The study aimed to provide a snapshot of this issue by focusing on two major periods of narrative crisis formation; however, this raises many more questions for future analysis, particularly in examining other periods reliant on crisis-centred narrative structures. The evolution of this phenomenon is only considered to an extent. Thus, future research is needed to provide a consistent account of the evolution of narrative frames, transcending the historical and extending this framework. As the ‘War on Terror’ is arguably an ongoing phenomenon, this framework could be augmented, covering the rhetorical and policy-centred transformations conducted through the Obama, Trump, and Biden periods. Moreover, as previously discussed, Trump’s use of anti-Communist rhetoric critically means the Communist threat is still a salient element of American crisis-formation. The narrative structures of crises persistently penetrate U.S. politics and continue to enable government expansion by means of militarising police forces. Thus, there is a need for renewed academic attention, not purely in the sphere of the economic or the technological, but in the rhetorical.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bush, G.W. (2001a). Address to the Nation on Operations in Afghanistan. Washington D.C.: White House. Available at: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/bushrecord/documents/Selected_Speeches_George_W_Bush.pdf (accessed 18/01/2024).

Bush, G.W. (2001b). Remarks on Signing the USA PATRIOT ACT of 2001. Washington D.C.: White House. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PPP-2001-book2/pdf/PPP-2001-book2-doc-pg1306.pdf (accessed 20/01/2024).

Bush, G.W. (2003). Remarks on the Freedom Agenda. United States Chamber of Commerce, Washington D.C. Available at: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/bushrecord/documents/Selected_Speeches_George_W_Bush.pdf (accessed 18/01/2024).

Bush, G.W. (2006a). Address to the Nation on the Fifth Anniversary of 9/11. Washington D.C.: White House. Available at: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/bushrecord/documents/Selected_Speeches_George_W_Bush.pdf (accessed 18/01/2024).

Bush, G.W. (2006b). President Signs USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorisation Act. White House: Washington D.C. Available at: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2006/03/20060309-4.html (accessed 18/01/2024).

Bush, G.W. (2006c). Remarks on the Global War on Terror: The Enemy in Their Own Words. Capitol Hilton Hotel, Washington D.C.: White House. Available at:https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/bushrecord/documents/Selected_Speeches_George_W_Bush.pdf (accessed 18/01/2024).

FBI (1968a). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 1. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1968b). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 2. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1968c). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 5. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1968d). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 6. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1968e). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 9. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1969a). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 11. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1969b). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 13. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1969c). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 16. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1969d). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 18. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1969e). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 20. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1969f). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 22. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

FBI (1969g). COINTELPRO, Black Extremist, Part 23. In FBI Records: The Vaults. Washington D.C. Available at: https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists (accessed 31/01/2024).

Hoover, J.E. (1956). Twin Enemies of Freedom. Address Before the 28th Annual Convention of the National Council of Catholic Women. Chicago, Illinois Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Hoover, J.E. (1958). Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It. San Francisco, UNITED STATES: Hauraki Publishing.

Hoover, J.E. (1962a). An American’s Challenge: Communism and Crime. National Convention of the American Legion, Las Vegas Nevada: Vital Speeches of the Day. Avaiable at: https://web-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=ef901b3c-ecb2-4e0e-ad70-65e02a13dc80%40redis (accessed 15/12/2023).

Hoover, J.E. (1962b). J. Edgar Hoover, Speech on Communism. Int. Assembly Hall, New York: Kinolibrary. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sjbQ7qAUCNk. (accessed 13/12/2023).

Hoover, J.E. (1964). FBI director J Edgar Hoover says FBI won’t protect civil rights workers. Office of Jackson Mississippi AP Archive. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5nfgzrkx5vA (accessed 13/12/2023).

Hoover, J.E. (1969). FBI Annual Report. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Available at: https://archive.org/details/fbiannualreport1969_202001/mode/2up (accessed 15/12/2023).

Petraeus, D.H., & Amos, J. F. (2006). Counterinsurgency FM 3-24 MCWP 3-33.5. In Army HDot (ed). Washington D.C.

The White House (2006). USA Patriot Act. Available at: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/patriotact/#:~:text=The%20Patriot%20Act%20allows%20Internet,monitoring%

20trespassers%20on%20their%20computers (accessed 22/02/2024).

Trump, D.J. (2020a). Black Lives Matter is a Marxist organisation that chants ‘pigs in a blanket, fry ‘em like bacon’. Donald J. Trump YouTube Channel. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MGGbmGuvBh8 (accessed 06/03/2024).

Trump, D.J. (2020b). President Trump: “Black Lives Matter is a marxist organisation… it’s bad for black people…. In Ingraham L (ed) Fox News. TrumpMedia. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TbQLhycaYLE (accessed 06/03/2024).

Trump, D.J. (2024). Voter’s Pamphlet: Washington State Elections Presidential Primary, March 12. In State So (ed). Washington State.

Secondary Sources

Ackerman, S. (2021). Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilised America and Produced Trump. New York: Penguin Random House.

Adachi, J. (2016). Police Militarization and the War on Citizens. Human Rights 42(1): 14-17.

Balto, S.E. (2013). “OCCUPIED TERRITORY”: POLICE REPRESSION AND BLACK RESISTANCE IN POSTWAR MILWAUKEE, 1950-1968. The Journal of African American History 98(2): 229-252.

Belew, K. (2018). Bring the war home the white power movement and paramilitary America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Berg, M. (2007). Black Civil Rights and Liberal Anticommunism: The NAACP in the Early Cold War. The Journal of American History 94(1): 75-96.

Brooks, R. (2014). The Trickle-Down War. Yale Law & Policy Review 32(2): 583-602.

Butler, J. (2009). Frames of war: when is life grievable?. London: Verso.

Carleton, D.E. (1987). “McCarthyism Was More Than McCarthy”: Documenting the Red Scare at the State and Local Level. The Midwestern Archivist 12(1): 13-19.

Churchill, W. and Vander Wall, J. (1990). The COINTELPRO papers: documents from the FBI’s secret wars against dissent in the United States. South End.

Darda, J. (2020). Empire of defense: race and the cultural politics of permanent war. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Delehanty C, Mewhirter J, Welch R, et al. (2017). Militarization and police violence: The case of the 1033 program. Research & Politics 4(2): 2053168017712885.

Dillard, J.E. (2012). Cultural Intelligence and Counterinsurgency Lessons from Vietnam, 1967-1971. American Intelligence Journal 30(1): 60-67.

Esch, J. (2010). Legitimizing the “War on Terror”: Political Myth in Official-Level Rhetoric. Political Psychology 31(3): 357-391.

Foster, S.J. (2000). Chapter II: The Power and Ubiquity of the Red Scare in American Post-War Culture. Counterpoints 87: 11-24.

Gamal, F. (2016). The Racial Politics of Protection: A Critical Race Examination of Police Militarization. California Law Review 104(4): 979-1008.

Gotham, K. (1992). A STUDY IN AMERICAN AGITATION: J. EDGAR HOOVER’S SYMBOLIC CONSTRUCTION OF THE COMMUNIST MENACE. Mid-American Review of Sociology 16(2): 57-70.

Gurman, H. (2013). Hearts and Minds: A People’s History of Counterinsurgency. New York: The New Press.

Haas, J. (2010). The assassination of Fred Hampton how the FBI and the Chicago police murdered a Black Panther. Chicago, Ill.: Lawrence Hill Books/Chicago Review Press.

Hall, A. R. & Coyne, C. J. (2013). The Militarization of U.S. Domestic Policing. The Independent Review, 17, 485-504.

Hetherington, M.J. and Nelson, M. (2003). Anatomy of a Rally Effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism. PS: Political Science and Politics 36(1): 37-42.

Higgs, R. (1987). Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government. New York: Oxford University Press.

Higgs, R. (2004). Against Leviathan: Government Power and a Free Society. Oakland, Calif: The Independent Institute

Higgs, R. (2006). Fear: The Foundation of Every Government’s Power. The Independent Review 10(3): 447-466.

Higgs, R. (2007). Neither Liberty nor Safety: Fear, Ideology and the Growth of Government. Oakland, California: The Independent Institute

Higgs, R. (2012). Delusions of Power: New Explorations of State, War, and Economy. California: The Independent Institute.

Hinton, E.K. (2021). America on fire: the untold history of police violence and black rebellion since the 1960s. London: William Collins.

Horne, G. (1986). Black and red: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Afro-American response to the Cold War, 1944-1963. State University of New York Press.

Howie, L. and Campbell, P. (2017). Crisis and Terror in the Age of Anxiety. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Jaccard, H. (2014). The wars come home: police militarization in the United States of America. Peace and freedom (1978) 74(2): 6.

Jones, D.P. (1978). From Military to Civilian Technology: The Introduction of Tear Gas for Civil Riot Control. Technology and Culture 19(2): 151-168.

Joseph, P.E. (2009). The Black Power Movement: A State of the Field. The Journal of American History 96(3): 751-776.

Katzenstein, J. (2020). The Wars Are Here: How the United States’ Post-9/11 Wars Helped Militarize U.S. Police. Watson Institute: International and Public Affairs. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown University.

Kellner, D. (2018). Donald Trump as Authoritarian Populist: A Frommian Analysis. In Morelock J (ed) Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism. University of Westminster Press, pp.71-82.

Kerner, O. (1967). Report of The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. In Disorders TNACoC (ed). Washington D.C.

Kishi, R. and Jones, S. (2020) DEMONSTRATIONS & POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN AMERICA, NEW DATA FOR SUMMER 2020. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

Kodosky, R.J. (2015). What’s in a Name? Waging War to Win Hearts and Minds. American Intelligence Journal 32(1): 172-180.

Kraska, P. (2007). Militarization and Policing—Its Relevance to 21st Century Police. Policing 1.

Kraska, P.B. (1996). Enjoying militarism: Political/personal dilemmas in studying U.S. police paramilitary units. Justice Quarterly 13(3): 405-429.

Kraska, P.B. and Cubellis, L.J. (1997). Militarizing mayberry and beyond: Making sense of American paramilitary policing. Justice Quarterly 14(4): 607-629.

Krebs, R.R. (2015). Narrative and the Making of US National Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lanham, A. (2021). The Geopolitics of American Policing. Michigan Law Review 119(1411): 1411-1430.

Lawson, E. (2019). TRENDS: Police Militarization and the Use of Lethal Force. Political Research Quarterly 72(1): 177-189.